SHIP BUILDING COMPETITION

(updated)

From the Naval and Military Magazine, vol I & vol II, June, September and December 1827.

___________________________________________________________

I am more grateful than he realizes to my friend, John Houghton (author of ‘Navies Of The World, 1835-1840’) for his gift of the first 4 volumes of this Magazine, which was to be renamed, with the fifth volume, the better-known “United Services Magazine”.

Until I read an article in the second number I had never heard of the sea trials, in 1827, of seven different sloops, representing the ideas of four different naval architects. When originally announced it was called a “Ship-building Competition”, and the vessels which took part later became known as the “Experimental Squadron”.

The first brief news item – 550 words – was buried in the ‘Miscellany’ section of the 2nd issue of the magazine, but there were further mentions of the results, which I’ve re-ordered slightly, following the first story. Most details of the sloops’ histories is from Lyons, ‘The Sailing Navy List’.

SHIP BUILDING COMPETITION (June, 1827)

On the 5th April Rear-Adm. Sir T. Hardy put to sea, from St. Helen's, in the Pyramus frigate, Capt. Geo. Rose Sartorius with the seven sail of experimental ships, viz.:

Tyne, 28, Capt. K. White;

Acorn, 18, Capt. Alex. Ellice; and

Satellite, 18, Capt. J. M. Laws - built by Sir R. Seppings;

Challenger 28, Capt. John Hayes, C.B. and

Wolf, 18, Capt. Geo. Hayes - built by Capt. Hayes;

Sapphire, 28, Capt. Henry Dundas - built by Professor Inman;

Columbine, 18, Capt. W. Symonds - built by that officer.

They were joined off Plymouth by the Trinculo brig.

The names of the respective designers certainly bear noticing. Seppings was at that time Surveyor of the Navy, to be succeeded in the post 5 years later by Symonds – at the time of this trial a humble Captain; between them they would chalk up 34 years as Surveyors.

Seppings had been a great innovator (he introduced diagonal bracing, which almost eliminated hogging) and his trial vessels rapidly became accepted as the new paradigm. Symonds – representing the next generation – fared rather worse. He was to be responsible for the elliptical stern – which strengthened the ships he later designed, as well as improving their arcs of fire. Symonds lacked professional training as a naval architect, and most of his designs were actually put down on paper by his assistant. In addition, he seemed to have become obsessed with sharp floors and beamy, 'stiff' ships.

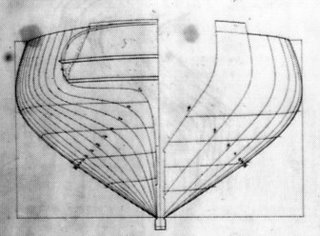

It doesn't take too much imagination to work out why a 'crank' or tender ship makes for a bad seaboat and gun platform: a short gust of wind laying a ship over suddenly could be more than alarming. But an excessively 'stiff' ship is almost equally undesirable. A vessel which is forever trying to overcome the pressure of wind to return to an upright state will be endangered, not by sudden gusts, but by equally sudden drops in the wind's strength. A ship that is too stiff will not be just a poor, unstable gun platform, she will also put unwarranted strain on masts and standing rigging, with a jerky, whiplash movement in anything but a mild, constant breeze. And this preoccupation of Symonds can be seen as early as this, the first trial (they were to continue, with other ships and other designers, for another 20 years). The Columbine (body section shown below) has the steep rise of floor that later characterized all his designs. And, as the account shows, because her gunports were a mere 3 feet from the waterline she was not considered a viable sea-boat; 4-5 feet was considered the minimum to enable using the lower ports in even a moderate sea. But somehow, with his patron's help, Symonds got the job as Surveyor on the resignation of Seppings, and later in his career, following the high costs and inherent problems of his designs, they gradually fell out of favour.

Two other designers are named: the Professor (James) Inman credited with the design of the 6th-rate Sapphire was the inaugural principal of the school of Naval Architecture, and had served an apprenticeship of sorts sailing as Flinders’ astronomer in 1803-4. The Sapphire was actually a group effort, designed & built by the best & brightest of the shipwright apprentices in his school. He was also the first translator, from the Swedish, of Chapman's 'Treatise on Shipbuilding'.

And the Captain Hayes who designed & commanded the Challenger, although now in his 50s, was the ‘Magnificent Hayes’ of seamanship fame who club-hauled his ship (the 74-gun HMS Magnificent) with such famous sang-froid in 1812 in Basque Roads to escape both the French and a lee-shore.

To Rear-Admiral Hardy fell the task of assessing the relative merits of each.

The ships sailed with the wind from the southward, but it was so light and variable, that they were more under the influence of the tide than of it, during the whole of the day. The ships will continue the cruise until Sir T. Hardy has satisfied himself, and convinced the respective commanders, which among them is the best ship of war, and in what degree the others ought to be relatively classed. For this purpose, we understand, the discriminating and experienced commander of the squadron will shift his flag to the fastest vessel on any point of sailing, and give the disputant competitors opportunity of again trying their skill and the rate of their ships.

They have been sent to sea with the utmost fairness toward the several scientific builders, and the Com.-in-Chief appointed to ascertain their merits, is universally acknowledged to combine with his other great professional merits, qualifications peculiar to such a service. The trial is considered of national importance.

The designers weren't content to just design sloops with different hull forms; other innovations were tried, with varying success. One of the greatest – and oldest – problems on sailing ships on long voyages was that of getting sufficient light and air into the tween-decks. Many scuttles, lights and ventilators were tried before the successful glass porthole-with-deadlight solved the issue, and a couple of the attempts had been incorporated into the designs. One of these relatively-new features sprang a leak in mid-trial:

On the 12th April, the Sapphire, 28, Capt. H. Dundas, came into Devonport from the experimental squadron, in consequence of the metal lids to her scuttles being leaky. The lids fitted on this principle have been for some time complained of in the service; it is to be hoped, therefore, that this additional proof of their not being effectual in keeping out the water will be an inducement for the Navy Board to adopt some of the several very excellent plans already before them. The Tyne has three or four scuttles fitted on a plan proposed by Lieut. Robertson, R. N., which were found completely tight, while the common scuttle lids were leaky.

Satellite (top). The profile of Columbine is shown below her body plan.

Satellite (top). The profile of Columbine is shown below her body plan.

Finally, all vessels functioning more or less normally and on station, the trials were run – but disappointingly, very little detail is given. The brig Trinculo was one of the numerous and successful Cruizer class, and Pyramus, Hardy’s ship, was considered a fast, weatherly frigate, her design having been based on the captured French Belle Poule, but with the upper-works of another French capture, the Nymphe. In spite of that it should be noted that all the sloops ‘sailed better than the Pyramus.’ In that sense it seems that all were successes, to a greater or lesser degree; apart from two which were wrecked, the average lifespan of these sloops was a very respectable 45 years. All were ship-rigged for the trials, except for the Columbine, which was a brig-sloop and, later in her career, a brigantine.

fast, weatherly frigate, her design having been based on the captured French Belle Poule, but with the upper-works of another French capture, the Nymphe. In spite of that it should be noted that all the sloops ‘sailed better than the Pyramus.’ In that sense it seems that all were successes, to a greater or lesser degree; apart from two which were wrecked, the average lifespan of these sloops was a very respectable 45 years. All were ship-rigged for the trials, except for the Columbine, which was a brig-sloop and, later in her career, a brigantine.

The Sapphire had been found to answer extremely well, and is considered a fine man of war of her class. When she left the squadron there had not been any order from the Admiral to try their rate of sailing, though they had been doing their best; but, from the wind being in general light and variable, little judgment could be formed as to the relative qualities of the experimental ships. On the first two days they were sailing by the wind, with light breezes, when it was considered that the Sapphire, Challenger and Columbine, were equal; the order of the others was - Wolf, Acorn, Satellite, and Tyne.

On the third day, when they had a strong breeze and some sea, sailing a point free, the Sapphire had considerably the advantage of the whole squadron, and the others were nearly in the same relative position as on the other two days. All the ships sail better than the Pyramus. The Sapphire is to rejoin the squadron immediately in Bantry Bay.

HMS Challenger was wrecked off the coast of Chile, eight years later, but nearly all its 160 crew were saved. HMS Acorn was lost somewhere in the Atlantic, 12 months later - almost to the day - with the loss of all 115 men on board. (For this, and details of other shipwrecks, see Gilly's 1850 book on the Gutenberg site.)

The Admiral Hardy who oversaw these trials was, of course, the same Hardy who had been Nelson’s Flag-Captain at Trafalgar; he had just returned from the South American station (where another of that breed, Lord Cochrane, would soon be making his own particular brand of mischief), and in 1830 was made First Sea Lord. The dinner-table conversations of the various captains turned shipbuilders – most of whom cut their teeth in the Napoleonic Wars which had finished a mere 12 years before - must have sparkled.

The Experimental Squadron (September, 1827)

In the September number, more details were made available, ending with the note that the squadron had embarked on a second experimental cruise, which was duly reported on in the December number.

We are indebted to an experienced naval officer for some authentic information relative to the proceedings of this little squadron during their recent cruize-the object of which, as our readers must have heard, was to ascertain the comparative sailing qualities of the several vessels, so as to enable the Board of Admiralty to judge of the claims of the respective projectors to superiority in ship-building; and we shall now lay it before our readers, with such additional particulars as we have been able to collect from other quarters.

The following is a list of the several vessels, with their number of guns, and the names of the officers upon whose plans the vessels have been built:

Challenger, 28 Guns, Capt. Hayes, C. B.

Columbine, 18 guns, Capt. Wm. Symonds.

Sapphire, 28 guns, The Shipwright Apprentices, R. N. College.

Wolf, 18 guns, Capt. Hayes.

Acorn, 18 guns, Sir Robert Seppings.

Satellite, 18 guns, Seppings.

Tyne, 28 guns, Seppings

These vessels sailed from St. Helens, on the 5th of April, under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy, K. C. B., who had his flag flying on board the Pyramus. They were subsequently joined by the Trinculo and Alert; and continued cruizing till the 25th of May, during which period they made twenty-two different trials. Some of the ships, however, were occasionally absent, to make good defects which they met with at sea, a circumstance which must be taken into consideration when judging of the result of the trials, which we mean to do as briefly, but, at the same time, as distinctly as possible.

The Challenger was the foremost ship in eleven out of the twenty-two trials; the Columbine was six times ahead out of twenty trials; the Sapphire three times out of sixteen trials; and the Wolf twice; but she was not absent during the whole cruize. On one occasion, we understand, in a cruize of about nine hours, the Challenger beat the Pyramus eight miles to windward.

The Wolf, Acorn, and Satellite, were generally considered to be of the same rate of sailing. Often trials which the Tyne (Sir Robert Seppings's ship) made, she was last eight times, and second last twice; in short, she was considered to be so very inferior to the other vessels in point of sailing, that it was deemed absolutely necessary some alteration should be made in her; and this was the cause of her having been present at only ten of the trials.

The Challenger does great credit to Captain Haves, being decidedly the best of the squadron; and it has afforded us much pleasure to hear that the Admiralty have rewarded the exertions of that ingenious officer, by a grant of £1,000; in addition to which, we understand, they have ordered his pay, as commander of the vessel, to be increased, so as to make it equal to that of Captain of a third rate.

The Columbine was considered by most of the officers, to rank next to the Challenger; the Sapphire next; and, as we said before, the Wolf, Acorn, and Satellite, were found to be pretty nearly equal. All the new ships (except the poor Tyne) are said to be superior to the Trinculo and Alert, and on several occasions they beat the Pyramus, a 42-gun frigate!

Since writing the above, the vessels have sailed on a second cruize, the result of which we hall not fail to lay before our readers, as soon as a sufficient time shall have elapsed to enable us to obtain all the particulars with due correctness.

Once the reports – spread over the 3 issues that appeared in June, September and December of 1827 – have been digested there are few surprises. The Columbine’s 3-feet clearance of her ports above the water-line was, to a generation brought up on the hard lessons of close blockade of the French coast, keeping Napoleon’s forces land-bound in all weathers, always going to be tricky if called upon to trundle out their great guns in any sort of sea.

Likewise, the extreme design of the Columbine, though stiff, was never going to inspire confidence in an officer of the watch tasked with keeping a chase in sight in choppy seas. And thus it turned out. Throughout the results the Columbine excels in ‘light airs’ but, once conditions get livelier, drops back and is beaten fair and square by just about every other vessel in the squadron.

THE EXPERIMENTAL SQUADRON, last report (December, 1827)

It is best to let the reports, speaking of trials conducted in the spring squalls of April and the autumn uncertainties of October’s cruise, speak for themselves.

THE EXPERIMENTAL SQUADRON, under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy, returned to Portsmouth on the 19th Oct from their third and last cruise,except the Tyne, which ship could not rejoin the squadron. We have in our last number given a detail of their proceedings, which we have reason to know was correct, and furnished n fair estimate of the respective qualities of the ships. To give, perfect satisfaction to all the parties concerned Is almost an impossibility ; for so identified, on all occasions, are both officers and seamen with their own ship, that if they do not absolutely distrust facts, they commonly see them through a very obscure and partial medium. There are, indeed, some cases, in which the inferiority of one ship is so evident, that no reasonable doubt can be entertained in the mind of any person - yet even in these cases, it often happens, that individuals so interested seek refuge in probabilities, instead of judging by plain facts. Thus, the most common reason assigned for failure, is - if the wind had not changed, a certain ship would have weathered all the squadron : and it is remarkable enough, that the wind is generally prejudicial to the ship concerned, for we have rarely heard it acknowledged that the wind favoured it.

Another excuse often urged is, that if such and such an accident had not happened, or if the trial had not unfortunately concluded just at the time the favourite vessel was fore-reaching or weathering on all the squadron, she would unquestionably have been the conqueror. But, the truth of the matter is, that shifts of wind and other casualties, in the long run, affect all the ships nearly alike; we shall not, therefore, take them into consideration, except, indeed, in such extraordinary cases as a ship carrying away a topmast, a yard, or an accident equally serious. In these instances, with reference to the vessel concerned, we need only inquire how she behaved previous to the accident, and, judge of her accordingly.

The squadron left St. Helen's on the 24th Sept, but returned in the evening; they weighed again on the 25th, and stood out to sea. On each occasion the wind was moderate. Of the 28's the Sapphire and Tyne beat the Challenger; the Columbine was superior to the rest of the squadron; we cannot, however, place much importance on these days, as tides may have favoured one ship and not another. We, however, thought it necessary to mention them, inasmuch as those were the only occasions on which the Tyne was present with the squadron.

Saturday, 29th Sept. At starting the wind was light, but afterwards blew half a gale. The Columbine bore up, through carrying away her iron gammoning; previous to this she beat all the squadron. Acorn weathered the Satellite a quarter of mile, Challenger and Wolf a mile, Alert five or six miles. Friday, Oct. 5: sailing two points free, under all possible sail. Columbine beat the Sapphire one mile, Satellite a mile and a half, Alert and Wolf two miles, Challenger and Acorn, two miles and a quarter. Saturday, October 6th” Close hauled, a calm, with occasional light winds. Columbine and Challenger weathered the Wolf, Satellite and Acorn, one-third of a mile, Sapphire two-thirds of a mile, Alert one mile.

Monday, Oct. 1: Close hauled, half a gale, with a heavy sea. The Acorn and Sapphire, when against the head sea, beat all the squadron; but on the other tack, when the wind lightened, and changed so as to bring the ships astern more to windward, Columbine weathered the Satellite half a mile, Acorn two-thirds of a mile, Sapphire a mile and a quarter, Challenger a mile and three-quarters, Wolf and Alert four miles.

Wednesday, Oct.10: Close-hauled, half a gale, with a head sea. The trial unexpectedly terminated, from the Challenger carrying away her main-topmast in tacking. While it continued, the Sapphire, Challenger, Columbine, Acorn, and Satellite, were nearly equal; but the Wolf and Alert were inferior to them.

Tuesday, Oct. 16th. Close-hauled, half a gale, with a head sea. During the trial the weather became so thick, that we cannot speak with certainty as to the result. However, the Satellite made signal that she weathered the Columbine half a mile; and the Acorn that she weathered the Satellite three-quarters of a mile. Before the weather became so thick, these ships had beaten the Sapphire considerably: the Alert and Wolf were hull down to leeward. The Challenger sprung her fore-yard, and is, therefore, not included in the trial. Previous to this accident she was beaten by the Columbine, Sapphire and Satellite.

From the behaviour of the ships when stowed for foreign service, it was evident that among the 28-gun frigates, the Sapphire had decidedly the advantage over the Challenger. Among the corvettes the Acorn, Satellite and Columbine, were equally Superior to the Wolf and Alert. It is evidently unfair to expect that the 28's should beat the corvettes, on account of the additional deck and carronades, with their top hamper. We are only surprised that they should have beaten them on any occasion, except sailing free.

We all know that fighting, as well as sailing, is an important quality in a man of war. It is rather singular that this indispensable quality should be generally overlooked, when dwelling on the efficiency of ships. But as the ships are nearly useless to the country, if they are unable to fight their lee and weather guns in heavy weather, we shall briefly allude to this property of the vessels under consideration. On Sept. the 29th, the Admiral made signal for the squadron to fire their guns; it was blowing very fresh, but not particularly so, as the squadron were carrying top-gallant sails. The .Acorn and Satellite fired with comparative ease, and might have engaged an enemy if required, even under her heavy press of sail. The Alert, Challenger, and Wolf, could not fire with any effect.

The Columbine and Sapphire were not in company at the time; we cannot, therefore, speak from experience of their capability of firing in bad weather. Any person, however, at all acquainted with the subject, must be aware that the Sapphire, from her stiffness, cannot be deficient in this respect; but that the Columbine, although very far from being crank, from the lowness of her ports, which are only three feet from the water, would, in a high sea, very probably fail in this material quality. On the whole, we think it fair to conclude that the Acorn, Satellite and Sapphire, judging of their general qualities as men of war, are among the finest ships of their respective classes in the British navy; that the chief exception against the Columbine is the lowness of her ports; and against the Challenger, Tyne and Wolf, deficiency in stability.

As stated, the more ‘experimental’, extreme design of Symonds (Columbine), did not fare very well at all when the wind had more than moderate force, or when there was any sort of sea running.

In fact the Columbine was never going to get approved as a model for a RN ship – one of those ‘storm-tossed ships’ which had to keep the seas in all weathers, and still be able to fight an action. Throughout the trials, whenever there was more than a cap-full of wind, she was bettered by all the other ships in the squadron.

And so the first of the ‘experimental squadrons’ completed its trials, under the patronage of the Duke of Clarence (later William IV) who, whatever his failings as a person, never failed the Navy, of which he was always ordinately proud to be a serving member. He gave his uncritical, enthusiastic support to every innovation, every improvement by which he believed the Navy would benefit, as will be seen in the final two, short pieces, both from the October ‘Miscellany’ pages of the Magazine.

the Lord High Admiral (Duke of Clarence), in a visit to Portsmouth, visited the “..new sloop of war Satellite, Capt. J. M. Laws (built by Sir R. Seppings), which is fitted with a new gun-carriage, the invention of Gen. Miller, improved by Sir T. Hardy, on a principle which admits of the gun being fired with considerably greater ease and facility than those which are mounted on the old carriages. H. R. H. was much pleased with the invention, and the exercise of the crew at the guns, as he was with the internal fitments and arrangements of the Satellite, which he minutely excamined. At half-past eleven H. R. H. left the sloop under a royal salute from the fleet, and landed from the steamer (HM steam-vessel Lightning) at Southsea Common.

The Lord High Admiral (Duke of Clarence) has directed Capt. J. Hayes and Capt. W. Symonds, each to build a 44-gun frigate, agreeably to their own plans, without any restrictions as to length, breadth or tonnage. Dr. Inman is to build another 28-gun frigate, which will be of greater length and breadth than ships of this force usually possess.